Climate Terminology Does Not Matter

Our new paper finds that swapping out one climate term for another does not meaningfully change people’s stated commitment to fight climate change

In a 2002 memo to the Republican party, consultant Frank Luntz is credited with advising the Bush administration that the phrase "global warming" should be abandoned in favour of "climate change", which he called "less frightening". Although he has since reversed his position on the issue of climate change, it remains an open question how much did this subtle shift in terminology impair the environmental movement.

For years, climate advocates, journalists, and policymakers have wrestled with which words best capture the seriousness of our overheating planet. Should we say “climate change,” or opt for heavier phrases like “climate crisis,” “climate emergency,” or even “global boiling”? Like Luntz, many have argued that these linguistic nuances might lead to greater public concern, shifting more people from apathy to action. But according to our recent global study published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology, the choice of terminology itself appears to have no measurable impact on people’s willingness to engage in climate action.

“our data suggest one main conclusion: swapping out one climate term for another does not meaningfully change people’s stated commitment to fight climate change”

Led by Danielle Goldwert, the papaer analyzed data from 63 countries. Despite differences in cultural background, political ideology, and demographic factors, our data suggest one main conclusion: swapping out one climate term for another does not meaningfully change people’s stated commitment to fight climate change.

The Power of Words?

Efforts to strategically shape public perception through language are nothing new. Historically, there has been a strong belief, known broadly as the theory of linguistic relativity, that specific words we choose can shape our beliefs and even behaviors. If language can alter how we think about space and color, proponents argued, it might also shift how we perceive the rising temperatures and intensifying storms of a warming planet.

Yet scientific findings on this front have been mixed. Some studies noted that people perceived “global warming” as more alarming than “climate change.” Others found no meaningful difference. Given these conflicting results, we took a broad look at whether updating climate terminology could lead to more commitment to climate solutions.

Experiment 1: A Global Perspective

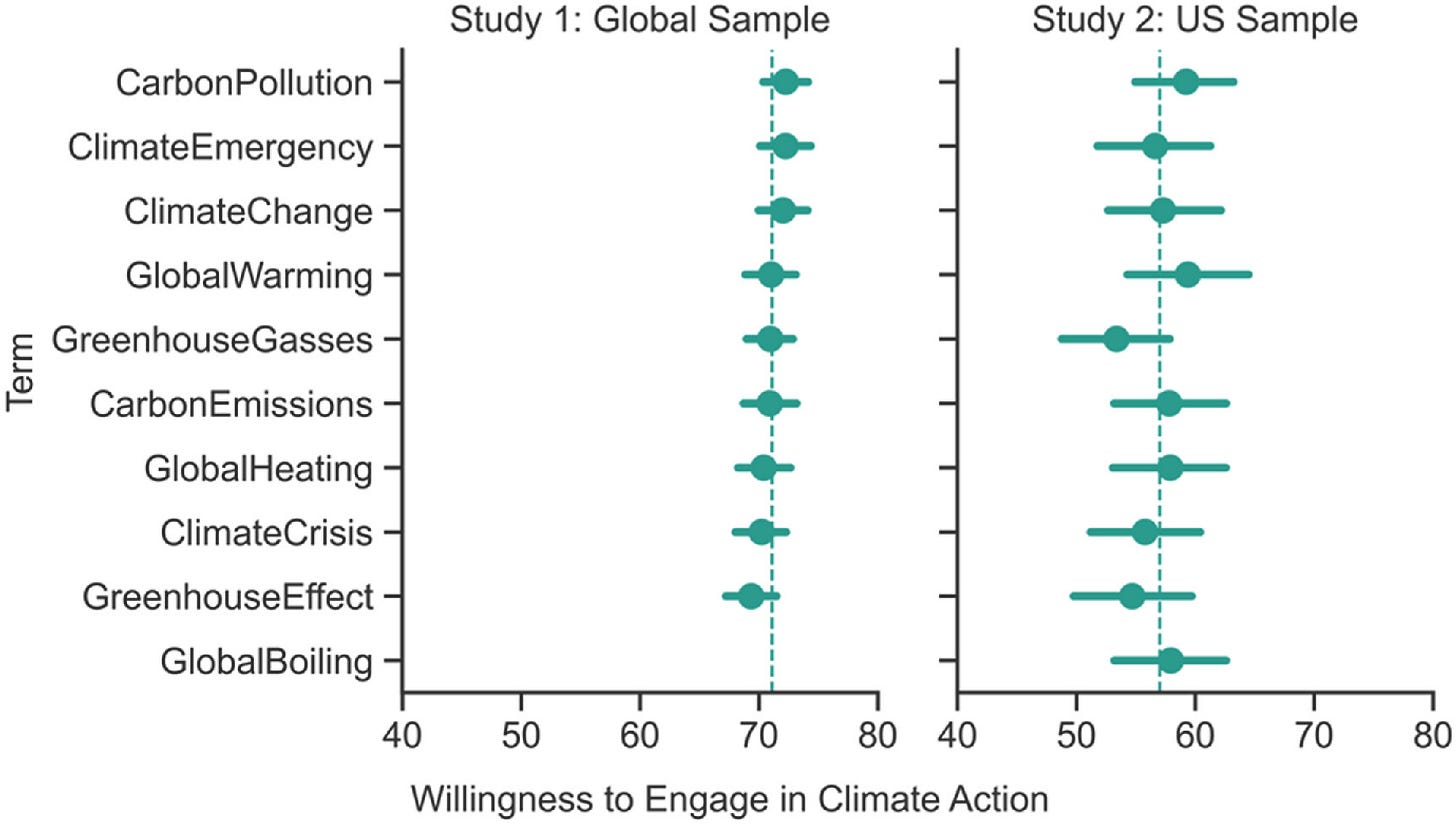

Our first experiment involved 4,531 participants across 63 countries. We tested nine common climate terms: “climate change,” “global warming,” “global heating,” “climate crisis,” “climate emergency,” “carbon pollution,” “carbon emissions,” “greenhouse gasses,” and “greenhouse effect.”

In a randomized design, each participant saw just one of these terms when asked about their willingness to take action: “To what degree are you willing to act to prevent [insert term here]?” Answers were collected on a 0 to 100 scale, where 0 meant “not at all” and 100 meant “very much so.”

Overall, the global sample reported high willingness to engage in climate action (on average, 74%). Despite this high baseline, there was no difference in motivation across the nine terms. Whether people read “climate crisis,” “global warming,” or “carbon emissions,” their responses about willingness to act barely moved. Bayesian statistical tests strongly supported this null result.

We further explored whether factors like political ideology, socioeconomic status, or gender would change how people responded to different terms. Again, nothing made a difference. For example, the terms resonated similarly among conservatives and liberals. This was surprising given previous findings suggesting that conservatives might dismiss “global warming” in favor of the more neutral “climate change.” Our larger, updated global dataset failed to replicate that pattern.

Experiment 2: A U.S. Replication

We then replicated our approach with 1,601 participants in the United States. This time, we added a tenth and more sensational term: “global boiling.” Yet again, the results were clear: no matter which of the 10 terms participants saw, their reported willingness to engage in climate action remained constant. Roughly 57% of the U.S. sample indicated willingness to take climate action, but none of the terminology increased (or decreased) that figure. Even “global boiling,” arguably the most urgent-sounding phrase, didn’t move the needle.

Key Takeaways

Across tens of thousands of participants in two large-scale experiments, labeling climate change in different ways had no effect on their stated willingness to act.

People, on average, are already quite concerned about climate change. The persistent threat we see in our daily weather, news coverage, and local experiences might overshadow subtle differences in wording.

Our global data showed similar null results across the political spectrum, challenging previous assumptions that conservatives react differently to “global warming” than “climate change.”

Resources spent debating the best phrase might be better used to drive tangible action. Messages that offer concrete steps or highlight success stories are more likely to inspire real change.

So What Does Matter?

Our findings don’t suggest that language has no role to play – after all, clear communication is vital for public understanding. But when it comes to prompting real behavioral change, the subtle difference between saying “climate change” vs. “climate crisis” vs. “global boiling” appears, at least for now, inconsequential.

This raises the question of where we should focus our efforts instead. We’d argue that calls to action might be more successful when they highlight:

Concrete, achievable steps for individuals and communities, such as carpooling, installing energy-efficient appliances, or organizing local tree-planting events.

Impactful solutions that people can connect to their daily lives, from rooftop solar to collective efforts to pass pro-climate legislation.

Visible role models (neighbors, local businesses, well-known figures) who are doing these things successfully, making change feel tangible and inspiring.

Community-building messages that emphasize shared values, mutual responsibility, and collective impact, reassuring people they’re not alone in their concerns or their actions.

By focusing on substantive strategies and actionable guidance, rather than the flashiest new phrase, climate communicators may see greater success mobilizing the public. In other words, it’s not about what we call it, but likely how we encourage people to tackle it.

Looking Ahead

This study doesn’t close the book on the relationship between language and climate action. Future research might explore repeated exposures to different terms over time, or whether new, more dramatic language shapes coverage and activism in subtle ways that aren’t captured in a single survey. But, our evidence strongly suggests that changing labels alone won’t galvanize the public to address climate change.

This also makes us wonder whether the obsessive debates over language that often dominate activist communities are really that meaningful. Perhaps their energy would be better spent taking action rather than debating—or policing—subtle differences in terminology. Before we join the bandwagon and re-label something it would be good practice to first see if the new label moves the needle.

For media outlets, advocacy organizations, and policymakers, these findings provide a valuable note of caution. Language certainly matters for clarity, accuracy, and credibility. However, if the end goal is to motivate action, then doubling down on how to act, rather than what to call it, may be the more productive path forward.

Reference

Goldwert, D., Doell, K. C., Van Bavel, J. J., & Vlasceanu, M. (2024). Climate change terminology does not influence willingness to take climate action. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 102482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2024.102482

News and Announcements

Jay will be giving a talk at the Learning and the Brain conference on April 25th in NYC; come check it out if you are in the city!

Steve Rathje, a postdoc in our lab, was a runner up for “Best Flash Talk” at the Society for Affective Science conference, out of 70 other talks given. Congrats to Steve!

This newsletter was written by Danielle Goldwert and edited by Anni Sternisko and Jay Van Bavel.

If you have any photos, news, or research you’d like to have included in this newsletter, please reach out to our Lab Manager Sarah (nyu.vanbavel.lab@gmail.com) who puts together our monthly newsletter. We encourage former lab members and collaborators to share exciting career updates or job opportunities—we’d love to hear what you’re up to and help sustain a flourishing lab community. Please also drop comments below about anything you like about the newsletter or would like us to add.

And in case you missed it, here’s our last newsletter:

That’s it for this month, folks - thanks for reading, and we’ll see you next month!

Thank you for conducting this important and impactful study, and for sharing the results. As a climate communications professional, I'm fully on board with your findings. The more attention we devote to bickering over the exact right term to use—especially among ourselves—the less we can devote to actually fixing the problem. As with most things in communication, the key is to know your audience, read the room—and, in particular, to LISTEN more than you speak, so you can respond in the most effective way possible. Your four pointers on what messages do work are about as spot-on as I can imagine, but require deeper engagement with the audience than most communicators are willing to put in—so you can find those solutions, role models, etc., that will ultimately resonate and drive change.

Thanks for sharing the results of this study.

Personally, I’m way further along the doomsday trajectory. For example, I consider the entire “reduce your footprint” message to be a gaslighting term literally introduced by an oil company, because it was.

The seriousness of the matter calls for radical action several orders if magnitude above the suggested actions.

Let me phrase that differently. If we do all the suggested actions, humanity still goes extinct. We’re already out of time and they don’t cut it.

I appreciate the well-meaning intentions and offer no solutions, other than increasing the panic level by a hundred.

Best wishes.